Halfway down the Adenauerallee in Bonn, the city that was home to the West German government from 1949 to 1990, there’s an anonymous modern office building, notable only for some sort of bookshop on the ground floor.

The building is home to a fascinating public body, the kind of which has no equivalent in the UK. It’s called the Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. The BpB for short. In English: the Federal Agency for Civic Education. On a rainy Thursday afternoon in July, I met Daniel Kraft, Director of Comms at BpB, who kindly took time out to explain the institution to me.

In this blogpost, I try to capture some of what it is and what it does. I then suggest that we need something similar in the UK, and I’m keen to hear ideas for bringing this about.

What is the BpB?

The mission of the Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung is to ‘strengthen democracy’. While the German constitution and its court provide judgements that protect the democratic process at the highest level, the BpB’s job is to build public support for the democratic system from the ground up. To ‘anchor’ support for democracy in the German population.

The mission is pursued through providing information and educational resources to audiences across different age groups via various magazines, books and leaflets as well as through events, videos and digital. The BpB has 200-staff and an annual budget of €42m to achieve this. It’s ‘subordinate’ to the Interior Ministry, which is interesting in terms of independence, and has advisory boards made up of politicians from all parties and of academics.

If you know more German than me, which seems likely, you might know that ‘education’ is not a perfect translation of Bildung. Bildung goes beyond schooling towards the idea of ‘self-cultivation’ and a ‘process of personal and cultural maturation’. (Thanks Wikipedia). This seems important. Perhaps it’s a problem that we don’t have an equivalent in English — we assume that education ends at school. That’s bad. I like the idea of civic education as a lifelong process in seeking to be a well-rounded person.

It reminds me of the fact that our trust in the way we are governed, which seems likely to be related to our knowledge of how we are governed, is provably part of our wellbeing, our contentedness and satisfaction with life. When we feel disenfranchised or we lack trust in the system, we become unhappier. And that’s when we start looking for alternatives, whether that’s on the far-left or far-right. We get post-truth politics. If we value democracy, we should be taking civic education very seriously indeed.

So how does the BpB do it?

Through content. Including a vast literature, from lesson plans to magazines for young adults to a series of books focusing on political issues of the day (e.g. “What is Populism?”).

This literature is available through BpB medienzentrums across Germany; the one in Bonn is designed on the lines of a stylish modern library or museum bookshop, with table football, coffee tables and booths in which to browse online materials. There are also shelves packed with attractively presented publications. I spotted magazines on topics such as Russia, drugs policy, immigration, Islam, refugees — you name it, the BpB has material on it. The books and magazines all appeared authoritative without being heavy, using punchy editorial and bold graphic design to give citizens an appealing way to improve their understanding of topical issues or of central tenets of Germany’s democratic system. If you can’t get to a medienzentrum you can order materials online.

And it’s not just literature. The BpB runs film and theatre festivals. It runs student competitions, and networks for young professionals. It hosts conferences, seminars and public lectures. It arranges study trips for journalists to Eastern Europe or Israel.

Increasingly, the BpB produces digital content, most notably the phenomenally successful voter advice application: Wahl-o-Mat. More on this — and the organisation’s digital efforts — in another post soon, but here’s a beauty vlogger doing civic education via YouTube. Good stuff.

Lastly, because it knows that a big federal agency isn’t going to be attractive to everyone, BpB funds over 80 civil society organisation projects on education. Following the principle of subsidiarity, it tries to ensure that the information comes from somewhere as close as possible to the citizen. A strong partnership strategy is critical to this kind of work.

What I liked was that the BpB doesn’t try to claim ‘neutrality’ or ‘objectivity’. Part of politische bildung is to help people understand that there is no such thing. The aim is to give people the information and arguments and help them to take a more informed decision. To help people understand the consequences of a political decision and, even better, that sometimes consequences are unpredictable. That governance is complex. People might leave a BpB event — or finish reading one of its magazines — feeling less clear than they were before, and that’s a good thing.

How was it created?

The earliest version of the BpB was founded in 1952 under Konrad Adenauer. I’d guessed that it was an attempt by the Allies to re-educate Germans in the values of democracy at the end of the war, but in fact it appears to have been more of homegrown preventative measure against the rise of communism, suggested by advisors to Adenauer.

There’s not an impetus as strong as this in the UK (yet). But perhaps the EU referendum experience — partly a culmination of the rejection of political elites, intellectual elites (‘we’ve had enough of experts’), perceived distance from Westminster, poor quality news reporting over decades, and a lack of accountability for those who made false arguments — can be the UK’s constitutional moment that forces us to look at how well we’re doing at democracy. We should be self-critical. Better to ask the hard questions now.

So how do we know the BpB helps?

Good question — I’ve not seen enough impact evaluation. I hope that this exists in the annual reports – but, reasonably, these are only available in German. The BpB can quote a few impressive figures, and Daniel Kraft reported that demand for material is consistently high. In 2015, for example:

- 20,000 Arabic-language versions of the constitution (or Basic Law) sold out immediately; and there were:

- 22.5m website visits,

- 360,000 views of partner videos on YouTube,

- 50,000 entrants to a student competition,

- 189,000 youth magazine subscribers, and

- 2,000 grants made to 80+ education institutions.

But these measure people who were already looking to learn; what about the disengaged?

Absolutely. It’s one of the trickiest problems affecting everyone who works in this field: how do you reach those people who don’t engage? The BpB works hard at this: for example, it actively organises meetings with members of Pegida, the far-right, anti-Islam organisation, who can’t be easy to engage with. The BpB works with Muslim communities too — and any other groups that might seem in danger of rejecting democratic politics.

The BpB is currently commissioning another survey of political knowledge across Germany, which will compare a baseline established 20 years ago. I’m presuming that longitudinal surveys are the best way to measure the impact of civic education, but there will be a range of positive effects of civic education that are hard to measure.

So why does the UK need this, and why now?

There are some excellent civil society organisations trying do various bits of this kind of work in the UK, but do they have the funding to do really strong work at scale? Can they attract great staff and provide a career for them? Do the materials all look fantastic, is the copy all well-written? There are significant benefits to having a large publicly funded institution doing this stuff, building a trusted brand, and assisting smaller organisations through resources or training.

Even with the larger organisations who take on parts of this work in the UK — such as the Houses of Parliament’s outreach and education team or maybe the Citizens Advice Bureau — there’s nobody looking at democracy holistically. It’s a patchwork of underfunded efforts.

Something like a UK BpB could also solve the problems we see at Democracy Club all the time: the lack of joined up democratic service provision, the opportunities afforded by digital technology that go begging. There are plenty of interesting potential media partners out there who want to do civic education work, but they can’t because no quality, trusted central data or content provider exists.

And why now? Well, I don’t think it can come soon enough. Brexit is the most glaring example of where our lack of civic education has let us down. Did people know what they were voting for? Were the arguments on both sides properly laid out in a clear, evidence-based fashion? Had the UK media adequately reported EU affairs for the last two decades? Was it good that the most searched Google topic the day after the referendum was ‘what is the EU?’ How can government, state and society function if the members of that society don’t understand how governance works or don’t have a grasp of a topical policy context?

Wait. A ‘publicly funded, independent’ institution that helps educate the public — this rings a bell. Isn’t the BBC supposed to do this stuff?

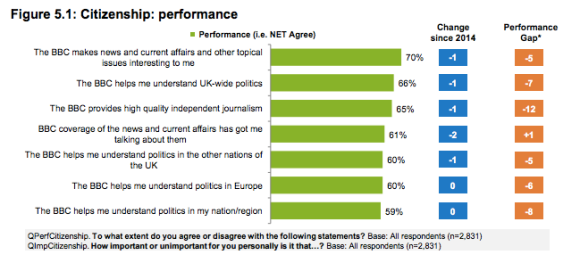

The BBC Charter outlines six public purposes. The very first one is to ‘sustain citizenship and civil society‘. So what is happening here? On the news side, the BBC’s concept of impartiality appears to involve playing a soundbite from each of the proposers and opposers of an argument and then throwing its hands up in the air. On the EU, it appeared to have abandoned explaining, providing context and actual reporting. Programmes such as Today in Parliament are great, but appeal to a highly selective audience on late-night Radio 4. What else can be done to engage more people in politics? And democracy more widely?

And that’s just the news media side: what other projects is the BBC doing to sustain citizenship and civil society? The BBC has shown such strength in digital innovation in other areas — thanks iPlayer team — so where are they on digital innovation in citizenship? It’s not clear.

Nor does it seem like the BBC measures its impact correctly. If I’m reading this wrong, correct me, but it seems like they measure the public’s perception of whether the BBC is sustaining citizenship, rather than the actual reality. Just because 65% of people agree that the BBC provides impartial journalism doesn’t mean that (a) it does and (b) that that journalism is helping to meet the public purpose. And impartial journalism is only one element of that first public remit.

It might be time for a new organisation to fulfil some of that role. Or at least to help the BBC to improve its efforts.

But don’t they teach Citizenship in schools?

‘Citizenship’ has existed on the national curriculum in some form since 2002. It seems to have gradually grown in importance since then, with detailed government guidelines published in 2013. Curiously, they include the guidance that teaching should prepare pupils to ‘manage their money well and make sound financial decisions.’ Hmm.

The Citizenship Foundation asks for more to be done, but seems fairly pleased with the status quo; on the other hand, I was told by a former teacher that citizenship in schools was becoming less of a priority. But whatever the state of citizenship education, it seems likely that it would only benefit from a well-funded, central organisation that could provide quality learning resources, conferences for teachers, study trips, independent evaluation of progress and so on.

Okay, I’m in. What next?

If you agree that there’s room for a new UK institution that produces quality information and educational content across a range of media to meet diverse audience needs, that also supports grassroots organisations and produces sustainable longitudinal evaluation of civic knowledge, then the next step is to think about institutional design:

- How would a UK BpB be independent from government, yet receive sustainable public funding? Is a university-style endowment model useful here?

- Who would govern it? Perhaps some kind of socially representative board that would include former politicians, academics, media representatives and citizens themselves?

- How would we measure its success? Can we go beyond turnout or reported civic knowledge? What else will show progress in UK politische bildung?

And how can we kickstart a conversation about such an institution for the UK?

Perhaps it takes some trusted ‘national treasure’ types — or a group of former newspaper editors, party leaders and education experts — to present the idea to the public via an op-ed, or letters to the editor? Or perhaps it could build on this related social media petition.

The design stage is also likely to need some amount of public subscription or private philanthropic funding before, as seems likely, it pursues government funding. And how quickly could it test some beta content?

If you have ideas to make this happen, or want to critique the idea, please get in touch. Presumably I’m not the first to suggest this; what happened to previous efforts? And any thoughts on the state of citizenship education or the BBC’s efforts — which I know too little about — are welcome too.

I’ll blog next on the BpB’s digital work, which is led from their Berlin office.

More detail on BpB’s activities can be found via their English-language pages.

Image credits: BpB.

7 replies on “Germany has a publicly funded agency with a mission to strengthen democracy. The UK needs one too.”

I’m in! Usually, particularly with the BBC, one has to point to the prevailing attitude toward macroeconomic policy and the state – the former collapses to austerity, leading to the rapid reduction in size and scope of the latter. Without proper funding and without a mature attitude toward what the public realm can (should, and needs to) do, then what hope for a UK BpB?

However, as you say, Brexit may have opened up new room, as it has in most other areas of politics. Maybe a first step, alongside building an address book of people along the lines you’ve given, is to have a version of this blogpost in, say, the FT, the Times etc, as well as the usual suspects, like the Guardian and the LRB. Get the (well written) word out to as much of the ‘elite’ a possible, they who are (hopefully) more open to all this than ever before.

You seem to forget that money provided to a government agency for such flimsy things as “strengthening democracy” can be used in ways that we would describe in economics as moral hazard. In fact, the BpB has been the dumping ground for outdated political advisers (Wolfgang Gibowski), it is heavily involved in campaigns against the so-called hatespeech, of which there exists no definition and hence, any organization is free to apply its own meaning, which makes the no-hate-speech campaign in Germany to the biggest left-wing endeavor to abandon free speech and replace it with correct speech, or what ever is deemed correct speech.

The BpB is furthermore used as a funding hub to channel money from official sources, say the Ministry for Family, Elderly, Women and Youth to political foundations, owned by political parties. This serves as a bypass, because the German Supreme Court ruled out direct funding of parties, that is why they fund political foundations owned by the political parties instead, with about 700m Euros per year.

In short, the BpB is a hub for corruption and the most important piece in a funding network that uses tax payers money to subsidize political activists.

Granted, the BpB produces a vast amount of material on a vast range of things and offers social scientists the chance to become known to politicians and political activists, which is useful for acquiring third party funding, via APUZ and other publications, but when it comes to political education, i’d rather say it is political indoctrination the BpB stands for.

I’ve been living in the UK for almost 10 years now and learned more about the second world war and the great war than in previous decades while living in Germany. I spend 13 years in the German school system and another 6 years at University, studying among other thing political science and as a consequence, I believe (and would provide evidence for this belief) that one documentary on History channel is more useful than one publication of the BpB.

Finally, as far as I see it, the British have no need for political education. Britain is an individual culture, not a collective one as Germany is. Britain has a long history in democracy and most people have a firm grip of what it is meant by the term democratic. By contrast, Germans learned about democracy after the II WW, having tried the system in the Weimar Republic and to a rather devastating effect, largely owed to the fact that almost all groups in society had no idea, what democracy is about and thought of it as a means to advance their respective ideology. (Some call democracy to this very day a Anglo-Saxon invention not suitable for Germans).

Maybe, after the II WW the BpB was useful as an institution to teach foundations of democratic life, something rather important as the OMGUS-studies conducted by the Americans after the II WW showed. However, the BpB did not prevent the Germans from again relapsing into the tune, once so vociferous in the Weimar Republic. Then, parties and organisations thought that democracy is a means to prevail with their ideology over their competition. And prevailing means getting rid of them, erasing or eliminating them. This is exactly the situation in Germany 2016 – despite the BpB or aided by the BpB.

Thank you very much for your hymn on the BpB. As a German political scientist (who is also involved in civic education) I assure: The BpB makes a great job.

Only one little caveat: Also the Weimar Republic had a similiar (but quite not such successful) institution called “Reichszentrale für Heimatdienst” (Agency for Homeland Information[?]; https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reichszentrale_f%C3%BCr_Heimatdienst). Also the BpB was called “Bundeszentrale für Heimatdienst” till 1963.

[…] with some caution it has to be said. But the real advance, I think, is his reference to the German system of trying to ensure that voters are well informed. This problem is at the core of those who either […]

The danger is that an institution like this will only strengthen the single mainstream expert view of things. An excellent example is :

“Brexit is the most glaring example of where our lack of civic education has let us down.”

Not all experts agree on that! The mainstream does, but “mainstream” is not equivalent to “right”, especially in social sciences like economy or politics . Therefore the debate is forced to be between the mainstream experts and “those that lack civic education”. In other words: those that disagree with mainstream experts, lack civic education. There is no room for nuance, for alternative yet informed views.

The lack of room for alternative yet informed views in politics and mainstream “quality” media and potentially in organisations like this, is a big problem. It forces nuanced thinkers to choose between two evils: arrogant mainstream experts and populists. No one should be forced to do that.

So let’s not make that mistake (again).

Definitely agree that that’s a risk that any institution would have to mitigate.

Around Brexit for example, remembering that on the day *after* the referendum, the most searched for term on Google was ‘What is the EU?’ — I think a civic education agency would have stepped in long before the referendum with a guide posted to all homes to answer that question. And so on.

In my opinion, the lack of scrutiny concerning the financial sector, economic science and the that way politics is intermingled with private interests, lead to a situation where most people feel loss and distrust.

The day after the 2008 crisis, the most frequent questions should have been: “How did this happen?”, “How could modern economics have missed this?”, “What is THE

economy?”, “What does GDP actually measure?”

But nobody *really* asked those questions. All criticism, especially from within the economic science, has been successfully ignored and now its news value is gone. Nothing fundamental has changed since. Neoclassical economics is still king, even though crisis can’t occur in their models and finance is an “unimportant” aspect that did, strange enough, create 95% of our Money (debt). Policies that follow from it still profits rent-seekers instead of entrepreneurs and people that work.

Most people do not profit from economic growth and face even more austerity and taxes. Most people don’t get it. Because the single mainstream expert view says it’s all good. Fortunately, things start to stir in the economics science and especially young scientists want a more heterodox education and a culture of debate. Like in real sciences. But the mainstream media are not picking it up just yet. Basically, they keep repeating the Fake News without proper investigation. So populism fills the gaps, with much juicier soundbites.

I hoped that recent referenda would wake up the political elite and the population. But just keep hearing it’s “the populists” and “fake news” and not those who caused these to thrive.